Quatro grandes invenções

As quatro grandes invenções (chinês tradicional: 四大發明, chinês simplificado: 四大发明, pinyin: sì dà fāmíng) são a bússola, a impressão, a fabricação de papel e a pólvora.[1] Estas invenções da China antiga que são celebradas na cultura chinesa pelo seu significado histórico e como símbolos da avançada ciência e tecnologia da China antiga.[2][3]

Essas quatro descobertas tiveram um enorme impacto no desenvolvimento da civilização chinesa e em um amplo impacto global. O filósofo inglês Francis Bacon, deixou escrito suas impressões sobre essas descobertas no Novum Organum:

- "Impressão, pólvora e bússola: Estas três mudaram toda a face e o estado das coisas em todo o mundo; a primeira na literatura, a segunda na guerra, a terceira na navegação; de onde se seguiram inúmeras mudanças, tanto que nenhum império, nenhuma seita, nenhuma estrela parece ter exercido maior poder e influência nos assuntos humanos do que essas descobertas mecânicas."[4]

- Bússola

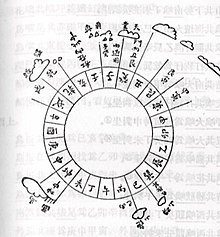

Uma bússola de magnetita foi usada na China durante a dinastia Han entre o século II aC e o primeiro século, onde foi chamada de "governadora do sul" (司南 sīnán).[5] Não foi usado para navegação, mas sim para geomancia e adivinhação.[6] Durante a maior parte da história chinesa, a bússola que permaneceu em uso estava na forma de uma agulha magnética flutuando em uma tigela de água.[7] De acordo com Needham, os chineses da dinastia Song e da Dinastia Yuan continuaram a usar uma bússola seca, embora este tipo nunca tenha se tornado tão amplamente usado na China quanto a bússola molhada.[8] A bússola seca usada na China era uma bússola de suspensão seca, uma estrutura de madeira trabalhada na forma de uma tartaruga pendurada de cabeça para baixo por uma tábua, com o ímã natural selado em cera e, se girado, a agulha na cauda da tartaruga apontaria sempre direção cardeal setentrional.[8] O desenho chinês da bússola seca suspensa persistiu em uso até o século XVIII.[9]

- Impressão

A invenção chinesa da impressão em xilogravura, em algum momento antes do primeiro livro datado de 868 (o Sutra do Diamante), produziu a primeira cultura impressa do mundo. De acordo com A. Hyatt Mayor, curador do Metropolitan Museum of Art, "foram os chineses que realmente descobriram os meios de comunicação que dominariam até a nossa era"[10] A impressão no norte da China avançou ainda mais no século XI, como foi escrito pelo cientista e estadista da dinastia Song, Shen Kuo (1031-1095),[11] que o artesão comum Bi Sheng (990-1051)[12] inventou a impressão do tipo móvel de cerâmica.[13]

A corte da Dinastia Qing patrocinou enormes projetos de impressão usando a impressão de tipo móvel em blocos de madeira durante o século XVIII. Embora substituída por técnicas de impressão ocidentais, a impressão do tipo móvel de blocos de madeira ainda permanece em uso em comunidades isoladas na China.[14]

- Papel

A produção de papel tem sido tradicionalmente atribuída à China por volta do ano 105, quando Cai Lun, funcionário da corte imperial durante a dinastia Han, criou uma folha de papel usando amoreira e outras fibras de entrecasca, junto com redes de arrastão, trapos e resíduos de cânhamo.[15] No entanto, uma recente descoberta arqueológica foi relatada a partir de Gansu de papel com caracteres chineses que datam de 8 aC.[16] No século VI, folhas de papel também estavam começando a ser usadas para papel higiênico.[17] Durante a dinastia Tang (618-907) o papel foi dobrado e costurado em sacos quadrados para preservar o sabor do chá.[18] A dinastia seguinte, a Song (960-1279), foi o primeiro governo a emitir papel-moeda.

- Pólvora

A pólvora foi descoberta no século IX pelos alquimistas chineses em busca de um elixir da imortalidade.[19] Na época em que o tratado da dinastia Song, Wujing Zongyao (武 经 总 要), foi escrito por Zeng Gongliang[20] e Yang Weide em 1044, as várias fórmulas chinesas para a pólvora continham níveis de nitrato na faixa de 27% a 50%.[21] No final do século XII, as fórmulas chinesas de pólvora tinham um nível de nitrato capaz de estourar através de recipientes de metal de ferro fundido, na forma das primeiras bombas de granadas ocas e cheias de pólvora.[22] Os chineses descobriram como criar explosivos redondos, embalando suas conchas vazias com esta pólvora enriquecida com nitrato.[22] Um tesouro escavado das antigas minas terrestres Ming mostrou que a pólvora misturada estava presente na China em 1370. Há evidências que sugerem que a pólvora pode ter sido usado no leste da Ásia desde o século XIII.[23]

Referências

- ↑ «The Four Great Inventions». China.org.cn. Consultado em 11 de novembro de 2007

- ↑ «Four Great Inventions of Ancient China -- Compass». ChinaCulture.org. Consultado em 11 de novembro de 2007. Arquivado do original em 9 de abril de 2007

- ↑ «Four Great Inventions of Ancient China -- Gunpowder». ChinaCulture.org. Consultado em 11 de novembro de 2007. Arquivado do original em 28 de agosto de 2007

- ↑ Novum Organum, Liber I, CXXIX - Traduzido e adaptado da tradução de 1863

- ↑ Merrill, Ronald T.; McElhinny, Michael W. (1983). The Earth's magnetic field: Its history, origin and planetary perspective 2nd printing ed. San Francisco: Academic press. p. 1. ISBN 0-12-491242-7

- ↑ Shu-hua, Li (Julho de 1954). «Origine de la Boussole 11. Aimant et Bousso». Oxford: Oxford Student Publications. Isis. 45: 175–196. doi:10.1086/348315

- ↑ Kreutz, p. 373

- ↑ a b Needham, IV 1, p. 255

- ↑ Needham, IV 1, p. 290

- ↑ A Hyatt Mayor (1971). Prints and People. Nos 1-4. Princeton: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-691-00326-2. Verifique

|isbn=(ajuda) - ↑ Needham, V 1, p. 201.

- ↑ Blue, Jennifer (25 de julho de 2007). «Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature». USGS. Consultado em 5 de agosto de 2007

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1994). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 4. [S.l.]: Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780521329958.

Bi Sheng... who first devised, about 1045, the art of printing with movable type

- ↑ Olympics bring unexpected luck to China's sole village using age-old movable-type printing, People's Daily

- ↑ «Papermaking». Encyclopædia Britannica. Consultado em 11 de novembro de 2007

- ↑ «World Archaeological Congress eNewsletter». 11 de agosto de 2006. Consultado em 11 de novembro de 2007. Arquivado do original em 6 de novembro de 2007

- ↑ Needham, V 1, p. 123

- ↑ Needham, V 1, p. 122

- ↑ Buchanan (2006), p. 42

- ↑ Zeng Gongliang

- ↑ Needham, V 7, pp. 345

- ↑ a b Needham, V 7, pp. 347

- ↑ Andrade (2016), p. 110

Fontes editar

- Adshead, Samuel Adrian Miles (2000), China in World History, ISBN 0-312-22565-2, London: MacMillan Press.

- Akira, Hirakawa (1998), A History of Indian Buddhism: From Sakyamani to Early Mahayana, ISBN 81-208-0955-6, traduzido por Paul Groner, New Delhi: Jainendra Prakash Jain At Shri Jainendra Press.

- An, Jiayao (2002), «When glass was treasured in China», in: Juliano, Annette L.; Lerner, Judith A., Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road, ISBN 2-503-52178-9, Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. 79–94.

- Bailey, H.W. (1985), Indo-Scythian Studies being Khotanese Texts Volume VII, ISBN 978-0-521-11992-4, Cambridge University Press.

- Balchin, Jon (2003), Science: 100 Scientists Who Changed the World, ISBN 1-59270-017-9, New York: Enchanted Lion Books.

- Ball, Warwick (2016), Rome in the East: Transformation of an Empire, ISBN 978-0-415-72078-6, London & New York: Routledge.

- Barbieri-Low, Anthony J. (2007), Artisans in Early Imperial China, ISBN 0-295-98713-8, Seattle & London: University of Washington Press.

- Barnes, Ian (2007), Mapping History: World History, ISBN 978-1-84573-323-0, London: Cartographica.

- Beck, Mansvelt (1986), «The fall of Han», in: Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 317–376.

- Berggren, Lennart; Borwein, Jonathan M.; Borwein, Peter B. (2004), Pi: A Source Book, ISBN 0-387-20571-3, New York: Springer.

- Bielenstein, Hans (1980), The Bureaucracy of Han Times, ISBN 0-521-22510-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ——— (1986), «Wang Mang, the Restoration of the Han Dynasty, and Later Han», in: Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 223–290.

- Block, Leo (2003), To Harness the Wind: A Short History of the Development of Sails, ISBN 1-55750-209-9, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

- Bower, Virginia (2005), «Standing man and woman», in: Richard, Naomi Noble, Recarving China's Past: Art, Archaeology and Architecture of the 'Wu Family Shrines', ISBN 0-300-10797-8, New Haven and London: Yale University Press and Princeton University Art Museum, pp. 242–245.

- Bowman, John S. (2000), Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture, ISBN 0-231-11004-9, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Buisseret, David (1998), Envisioning the City: Six Studies in Urban Cartography, ISBN 0-226-07993-7, Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

- Bulling, A. (1962), «A landscape representation of the Western Han period», Artibus Asiae, 25 (4): 293–317, JSTOR 3249129.

- Chang, Chun-shu (2007), The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Volume II; Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157, ISBN 0-472-11534-0, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Chavannes, Édouard (1907), «Les pays d'Occident d'après le Heou Han chou» (PDF), T'oung pao, 8: 149–244.

- Ch'en, Ch'i-Yün (1986), «Confucian, Legalist, and Taoist thought in Later Han», in: Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 766–806.

- Ch'ü, T'ung-tsu (1972), Dull, Jack L., ed., Han Dynasty China: Volume 1: Han Social Structure, ISBN 0-295-95068-4, Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.

- Chung, Chee Kit (2005), «Longyamen is Singapore: The Final Proof?», Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia, ISBN 981-230-329-4, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Cotterell, Maurice (2004), The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor's Army, ISBN 1-59143-033-X, Rochester: Bear and Company.

- Cribb, Joe (1978), «Chinese lead ingots with barbarous Greek inscriptions», London, Coin Hoards, 4: 76–78.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mark (2006), Readings in Han Chinese Thought, ISBN 0-87220-710-2, Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company.

- Cullen, Christoper (2006), Astronomy and Mathematics in Ancient China: The Zhou Bi Suan Jing, ISBN 0-521-03537-6, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cutter, Robert Joe (1989), The Brush and the Spur: Chinese Culture and the Cockfight, ISBN 962-201-417-8, Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Dauben, Joseph W. (2007), «Chinese Mathematics», in: Katz, Victor J., The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook, ISBN 0-691-11485-4, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 187–384.

- Davis, Paul K. (2001), 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present, ISBN 0-19-514366-3, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Day, Lance; McNeil, Ian (1996), Biographical Dictionary of the History of Technology, ISBN 0-415-06042-7, New York: Routledge.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007), A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD), ISBN 90-04-15605-4, Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

- Demiéville, Paul (1986), «Philosophy and religion from Han to Sui», in: Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 808–872.

- Deng, Yingke (2005), Ancient Chinese Inventions, ISBN 7-5085-0837-8, traduzido por Wang Pingxing, Beijing: China Intercontinental Press (五洲传播出版社).

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (2002), Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History, ISBN 0-521-77064-5, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1974), «Estate and family management in the Later Han as seen in the Monthly Instructions for the Four Classes of People», Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 17 (2): 173–205, JSTOR 3596331.

- ——— (1986), «The Economic and Social History of Later Han», in: Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 608–648.

- ——— (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, ISBN 0-521-66991-X, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fairbank, John K.; Goldman, Merle (1998), China: A New History, Enlarged Edition, ISBN 0-674-11673-9, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Fraser, Ian W. (2014), «Zhang Heng 张衡», in: Brown, Kerry, The Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography, ISBN 1-933782-66-8, Great Barrington: Berkshire Publishing.

- Greenberger, Robert (2006), The Technology of Ancient China, ISBN 1-4042-0558-6, New York: Rosen Publishing Group.

- Guo, Qinghua (2005), Chinese Architecture and Planning: Ideas, Methods, and Techniques, ISBN 3-932565-54-1, Stuttgart and London: Edition Axel Menges.

- Hansen, Valerie (2000), The Open Empire: A History of China to 1600, ISBN 0-393-97374-3, New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Hardy, Grant (1999), Worlds of Bronze and Bamboo: Sima Qian's Conquest of History, ISBN 0-231-11304-8, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hill, John E. (2009), Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries AD, ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1, Charleston, South Carolina: BookSurge.

- Hinsch, Bret (2002), Women in Imperial China, ISBN 0-7425-1872-8, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Hsu, Cho-Yun (1965), «The changing relationship between local society and the central political power in Former Han: 206 B.C. – 8 A.D.», Comparative Studies in Society and History, 7 (4): 358–370, doi:10.1017/S0010417500003777.

- Hsu, Elisabeth (2001), «Pulse diagnostics in the Western Han: how mai and qi determine bing», in: Hsu, Elisabeth, Innovations in Chinese Medicine, ISBN 0-521-80068-4, Cambridge, New York, Oakleigh, Madrid, and Cape Town: Cambridge University Press, pp. 51–92.

- Hsu, Mei-ling (1993), «The Qin maps: a clue to later Chinese cartographic development», Imago Mundi, 45: 90–100, doi:10.1080/03085699308592766.

- Huang, Ray (1988), China: A Macro History, ISBN 0-87332-452-8, Armonk & London: M.E. Sharpe.

- Hulsewé, A.F.P. (1986), «Ch'in and Han law», in: Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 520–544.

- Jin, Guantao; Fan, Hongye; Liu, Qingfeng (1996), «Historical Changes in the Structure of Science and Technology (Part Two, a Commentary)», in: Dainian, Fan; Cohen, Robert S., Chinese Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, ISBN 0-7923-3463-9, traduzido por Kathleen Dugan and Jiang Mingshan, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 165–184.

- Knechtges, David R. (2010), «From the Eastern Han through the Western Jin (AD 25–317)», in: Owen, Stephen, The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, volume 1, ISBN 978-0-521-85558-7, Cambridge University Press, pp. 116–198.

- Ho, Kenneth Pui-Hung (1986). «Yang Hsiung 揚雄». In: Nienhauser, William. The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature, Volume 1. Bloomfield: Indiana University Press. pp. 912–913

- ——— (2014), «Zhang Heng 張衡», in: Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping, Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part Four, ISBN 978-90-04-27217-0, Leiden: Brill, pp. 2141–55.

- Kramers, Robert P. (1986), «The development of the Confucian schools», in: Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 747–756.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007), The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han, ISBN 0-674-02477-X, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Liu, Xujie (2002), «The Qin and Han dynasties», in: Steinhardt, Nancy S., Chinese Architecture, ISBN 0-300-09559-7, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 33–60.

- Liu, Guilin; Feng, Lisheng; Jiang, Airong; Zheng, Xiaohui (2003), «The Development of E-Mathematics Resources at Tsinghua University Library (THUL)», in: Bai, Fengshan; Wegner, Bern, Electronic Information and Communication in Mathematics, ISBN 3-540-40689-1, Berlin, Heidelberg and New York: Springer Verlag, pp. 1–13.

- Lloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard (1996), Adversaries and Authorities: Investigations into Ancient Greek and Chinese Science, ISBN 0-521-55695-3, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lo, Vivienne (2001), «The influence of nurturing life culture on the development of Western Han acumoxa therapy», in: Hsu, Elisabeth, Innovation in Chinese Medicine, ISBN 0-521-80068-4, Cambridge, New York, Oakleigh, Madrid and Cape Town: Cambridge University Press, pp. 19–50.

- Loewe, Michael (1968), Everyday Life in Early Imperial China during the Han Period 202 BC–AD 220, ISBN 0-87220-758-7, London: B.T. Batsford.

- ——— (1986), «The Former Han Dynasty», in: Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 103–222.

- ——— (1994), Divination, Mythology and Monarchy in Han China, ISBN 0-521-45466-2, Cambridge, New York and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- ——— (2005), «Funerary Practice in Han Times», in: Richard, Naomi Noble, Recarving China's Past: Art, Archaeology, and Architecture of the 'Wu Family Shrines', ISBN 0-300-10797-8, New Haven and London: Yale University Press and Princeton University Art Museum, pp. 23–74.

- ——— (2006), The Government of the Qin and Han Empires: 221 BCE–220 CE, ISBN 978-0-87220-819-3, Hackett Publishing Company.

- Mawer, Granville Allen (2013), «The Riddle of Cattigara», in: Robert Nichols and Martin Woods, Mapping Our World: Terra Incognita to Australia, ISBN 978-0-642-27809-8, Canberra: National Library of Australia, pp. 38–39.

- McClain, Ernest G.; Ming, Shui Hung (1979), «Chinese cyclic tunings in late antiquity», Ethnomusicology, 23 (2): 205–224, JSTOR 851462.

- Morton, William Scott; Lewis, Charlton M. (2005), China: Its History and Culture, ISBN 0-07-141279-4 Fourth ed. , New York City: McGraw-Hill.

- Needham, Joseph (1972), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 1, Introductory Orientations, ISBN 0-521-05799-X, London: Syndics of the Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1962). Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Col: Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 4. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph, ed. (1985). Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Tsien Hsuen-Hsuin, Paper and Printing. Col: Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph, ed. (1994). Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Robin D.S. Yates, Krzysztof Gawlikowski, Edward McEwen, Wang Ling (collaborators) Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Col: Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- ——— (1986a), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3; Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, ISBN 0-521-05801-5, Taipei: Caves Books.

- ——— (1986b), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology; Part 1, Physics, ISBN 0-521-05802-3, Taipei: Caves Books.

- ——— (1986c), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology; Part 2, Mechanical Engineering, ISBN 0-521-05803-1, Taipei: Caves Books.

- ——— (1986d), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics, ISBN 0-521-07060-0, Taipei: Caves Books.

- Needham, Joseph; Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1986), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing, ISBN 0-521-08690-6, Taipei: Caves Books.

- Needham, Joseph (1988), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 9, Textile Technology: Spinning and Reeling, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Neinhauser, William H.; Hartman, Charles; Ma, Y.W.; West, Stephen H. (1986), The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature: Volume 1, ISBN 0-253-32983-3, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Nelson, Howard (1974), «Chinese maps: an exhibition at the British Library», The China Quarterly, 58: 357–362, doi:10.1017/S0305741000011346.

- Nishijima, Sadao (1986), «The economic and social history of Former Han», in: Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 545–607.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, ISBN 0-521-29653-6, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Omura, Yoshiaki (2003), Acupuncture Medicine: Its Historical and Clinical Background, ISBN 0-486-42850-8, Mineola: Dover Publications.

- O'Reilly, Dougald J.W. (2007), Early Civilizations of Southeast Asia, ISBN 0-7591-0279-1, Lanham, New York, Toronto, Plymouth: AltaMira Press, Division of Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

- Paludan, Ann (1998), Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors: the Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial China, ISBN 0-500-05090-2, London: Thames & Hudson.

- Pigott, Vincent C. (1999), The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World, ISBN 0-924171-34-0, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

- Ronan, Colin A (1994), The Shorter Science and Civilization in China: 4, ISBN 0-521-32995-7, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (an abridgement of Joseph Needham's work)

- Schaefer, Richard T. (2008), Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society: Volume 3, ISBN 1-4129-2694-7, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.

- Shen, Kangshen; Crossley, John N.; Lun, Anthony W.C. (1999), The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art: Companion and Commentary, ISBN 0-19-853936-3, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman (2004), «The Tang architectural icon and the politics of Chinese architectural history», The Art Bulletin, 86 (2): 228–254, JSTOR 3177416, doi:10.1080/00043079.2004.10786192.

- ——— (2005a), «Pleasure tower model», in: Richard, Naomi Noble, Recarving China's Past: Art, Archaeology, and Architecture of the 'Wu Family Shrines', ISBN 0-300-10797-8, New Haven and London: Yale University Press and Princeton University Art Museum, pp. 275–281.

- ——— (2005b), «Tower model», in: Richard, Naomi Noble, Recarving China's Past: Art, Archaeology, and Architecture of the 'Wu Family Shrines', ISBN 0-300-10797-8, New Haven and London: Yale University Press and Princeton University Art Museum, pp. 283–285.

- Straffin, Philip D., Jr (1998), «Liu Hui and the first Golden Age of Chinese mathematics», Mathematics Magazine, 71 (3): 163–181, JSTOR 2691200.

- Suárez, Thomas (1999), Early Mapping of Southeast Asia, ISBN 962-593-470-7, Singapore: Periplus Editions.

- Sun, Xiaochun; Kistemaker, Jacob (1997), The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society, ISBN 90-04-10737-1, Leiden, New York, Köln: Koninklijke Brill.

- Taagepera, Rein (1979), «Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.», Social Science History, 3 (3/4): 115–138, JSTOR 1170959.

- Teresi, Dick (2002), Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science–from the Babylonians to the Mayas, ISBN 0-684-83718-8, New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Thorp, Robert L. (1986), «Architectural principles in early Imperial China: structural problems and their solution», The Art Bulletin, 68 (3): 360–378, JSTOR 3050972.

- Tom, K.S. (1989), Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Middle Kingdom, ISBN 0-8248-1285-9, Honolulu: The Hawaii Chinese History Center of the University of Hawaii Press.

- Torday, Laszlo (1997), Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History, ISBN 1-900838-03-6, Durham: The Durham Academic Press.

- Turnbull, Stephen R. (2002), Fighting Ships of the Far East: China and Southeast Asia 202 BC–AD 1419, ISBN 1-84176-386-1, Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

- Wagner, Donald B. (1993), Iron and Steel in Ancient China, ISBN 978-90-04-09632-5, Brill.

- ——— (2001), The State and the Iron Industry in Han China, ISBN 87-87062-83-6, Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Publishing.

- Wang, Yu-ch'uan (1949), «An outline of The central government of the Former Han dynasty», Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 12 (1/2): 134–187, JSTOR 2718206.

- Wang, Zhongshu (1982), Han Civilization, ISBN 0-300-02723-0, traduzido por K.C. Chang and Collaborators, New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Wang, Xudang; Li, Zuixiong; Zhang, Lu (2010), «Condition, Conservation, and Reinforcement of the Yumen Pass and Hecang Earthen Ruins Near Dunhuang», in: Neville Agnew, Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China, June 28 – July 3, 2004, ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1, pp. 351–352 [351–357].

- Watson, William (2000), The Arts of China to AD 900, ISBN 0-300-08284-3, New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. (2011) [2001], Gender in History: Global Perspectives, ISBN 978-1-4051-8995-8 2nd ed. , Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell

- Xue, Shiqi (2003), «Chinese lexicography past and present», in: Hartmann, R.R.K., Lexicography: Critical Concepts, ISBN 0-415-25365-9, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 158–173.

- Young, Gary K. (2001), Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC – AD 305, ISBN 0-415-24219-3, London & New York: Routledge.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1967), Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-Barbarian Economic Relations, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ——— (1986), «Han foreign relations», in: Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 377–462.

- Yule, Henry (1915), Henri Cordier, ed., Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route, 1, London: Hakluyt Society.

- Zhang, Guangda (2002), «The role of the Sogdians as translators of Buddhist texts», in: Juliano, Annette L.; Lerner, Judith A., Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road, ISBN 2-503-52178-9, Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. 75–78.

- Zhou, Jinghao (2003), Remaking China's Public Philosophy for the Twenty-First Century, ISBN 0-275-97882-6, Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group.